For many people placing a nine-volt battery on their tongue, like sex, can be a fun, exciting activity, sometimes resulting in death. Based on this observation, Reinhart and Woodman (2014) decided to turn the brain into an improvised battery by placing electrodes on different areas of the skull and zapping it with enough current to toast a frozen hotpocket. If this sounds insane to you, then you are obviously not a cognitive neuroscientist - as I have said before, we live for these kinds of experiments.

However, the researchers had good reasons for doing this. First of all, they are scientists, and they did not spend nine years on their doctorate only to justify themselves to the likes of you. Second, directly messing with brain activity can lead to valuable scientific insights, such as how much you have to pay an undergraduate to have them consent to turn their brain into a microwave oven. But third, and most important, delivering direct current through a pair of electrodes can increase or decrease certain patterns of neural activity - specifically, the error-related negativity (ERN) following an error trial.

The ERN is a negative deflection in voltage over the medial frontal lobes that correlates with behavior adjustment and error correction in the future. For example, if I commit what some narrow-minded, parochial individuals consider an error, such as asking out my girlfriend's sister, the larger my ERN is, the less likely I am to make that same mistake in the future. Similarly, with experiments such as the Stroop task, or any performance task, the larger the ERN after committing an error, the greater the probability of making a correct response on the next trial. Furthermore, whereas the ERN usually occurs immediately after the response is made, another related signal, the feedback related negativity (FRN) occurs once feedback is received. In sum, larger ERNs and FRNs generally lead to better future performance.

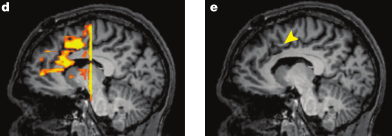

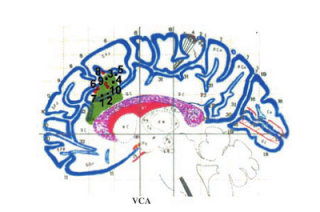

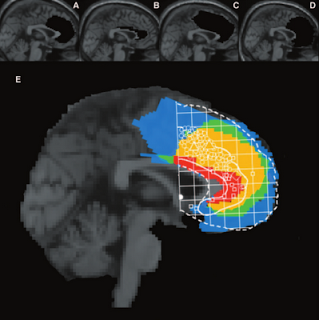

This is exactly what the experimenters manipulated when they sent current through the medial frontal area of the brain, corresponding to the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and supplementary motor area (SMA) cortical regions. The electrode over this area was changed to either a cathode (i.e., positively charged, or where the electrons flowed toward) or an anode (i.e., negatively charged, or where the electrons flowed away from). If the electrode was a cathode, the ERN decreased significantly, whereas if the electrode was an anode, the ERN significantly increased.

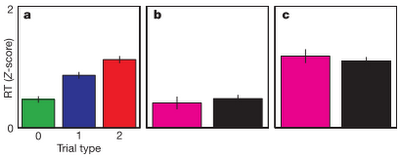

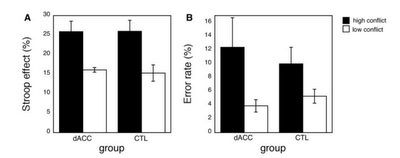

As interesting as these neural differences are, however, the real punch of the paper lies in the behavioral changes. Participants who had an anode placed over their cingulate and SMA areas not only showed greater ERN and FRN profiles, but also steep gains in their accuracy and improvements in reaction time. For regular trials which did not include a distracting stop signal, anode subjects were markedly faster than in the cathode and sham conditions, and in both regular and stop-signal trials, accuracy nearly reached a hundred percent.

Nor were these gains limited to the duration of the experiment; in fact, behavioral improvements could last as long as five hours after switching on the current. These results make for wild and reckless speculations about what could be done with this kind of setup; one could imagine creating caps for students which get them "juiced up" for exams, hats for the elderly to help them find their Mysteriously Disappearing Reading Glasses, or modified helmets for soldiers which allow them get even better at BSU (blowing stuff up). Because, after all, what's the use of a scientific result if you can't weaponize it?

More figures and results from experiments further extending and confirming their results can be seen in the paper, found here.

However, the researchers had good reasons for doing this. First of all, they are scientists, and they did not spend nine years on their doctorate only to justify themselves to the likes of you. Second, directly messing with brain activity can lead to valuable scientific insights, such as how much you have to pay an undergraduate to have them consent to turn their brain into a microwave oven. But third, and most important, delivering direct current through a pair of electrodes can increase or decrease certain patterns of neural activity - specifically, the error-related negativity (ERN) following an error trial.

The ERN is a negative deflection in voltage over the medial frontal lobes that correlates with behavior adjustment and error correction in the future. For example, if I commit what some narrow-minded, parochial individuals consider an error, such as asking out my girlfriend's sister, the larger my ERN is, the less likely I am to make that same mistake in the future. Similarly, with experiments such as the Stroop task, or any performance task, the larger the ERN after committing an error, the greater the probability of making a correct response on the next trial. Furthermore, whereas the ERN usually occurs immediately after the response is made, another related signal, the feedback related negativity (FRN) occurs once feedback is received. In sum, larger ERNs and FRNs generally lead to better future performance.

This is exactly what the experimenters manipulated when they sent current through the medial frontal area of the brain, corresponding to the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and supplementary motor area (SMA) cortical regions. The electrode over this area was changed to either a cathode (i.e., positively charged, or where the electrons flowed toward) or an anode (i.e., negatively charged, or where the electrons flowed away from). If the electrode was a cathode, the ERN decreased significantly, whereas if the electrode was an anode, the ERN significantly increased.

As interesting as these neural differences are, however, the real punch of the paper lies in the behavioral changes. Participants who had an anode placed over their cingulate and SMA areas not only showed greater ERN and FRN profiles, but also steep gains in their accuracy and improvements in reaction time. For regular trials which did not include a distracting stop signal, anode subjects were markedly faster than in the cathode and sham conditions, and in both regular and stop-signal trials, accuracy nearly reached a hundred percent.

Nor were these gains limited to the duration of the experiment; in fact, behavioral improvements could last as long as five hours after switching on the current. These results make for wild and reckless speculations about what could be done with this kind of setup; one could imagine creating caps for students which get them "juiced up" for exams, hats for the elderly to help them find their Mysteriously Disappearing Reading Glasses, or modified helmets for soldiers which allow them get even better at BSU (blowing stuff up). Because, after all, what's the use of a scientific result if you can't weaponize it?

More figures and results from experiments further extending and confirming their results can be seen in the paper, found here.